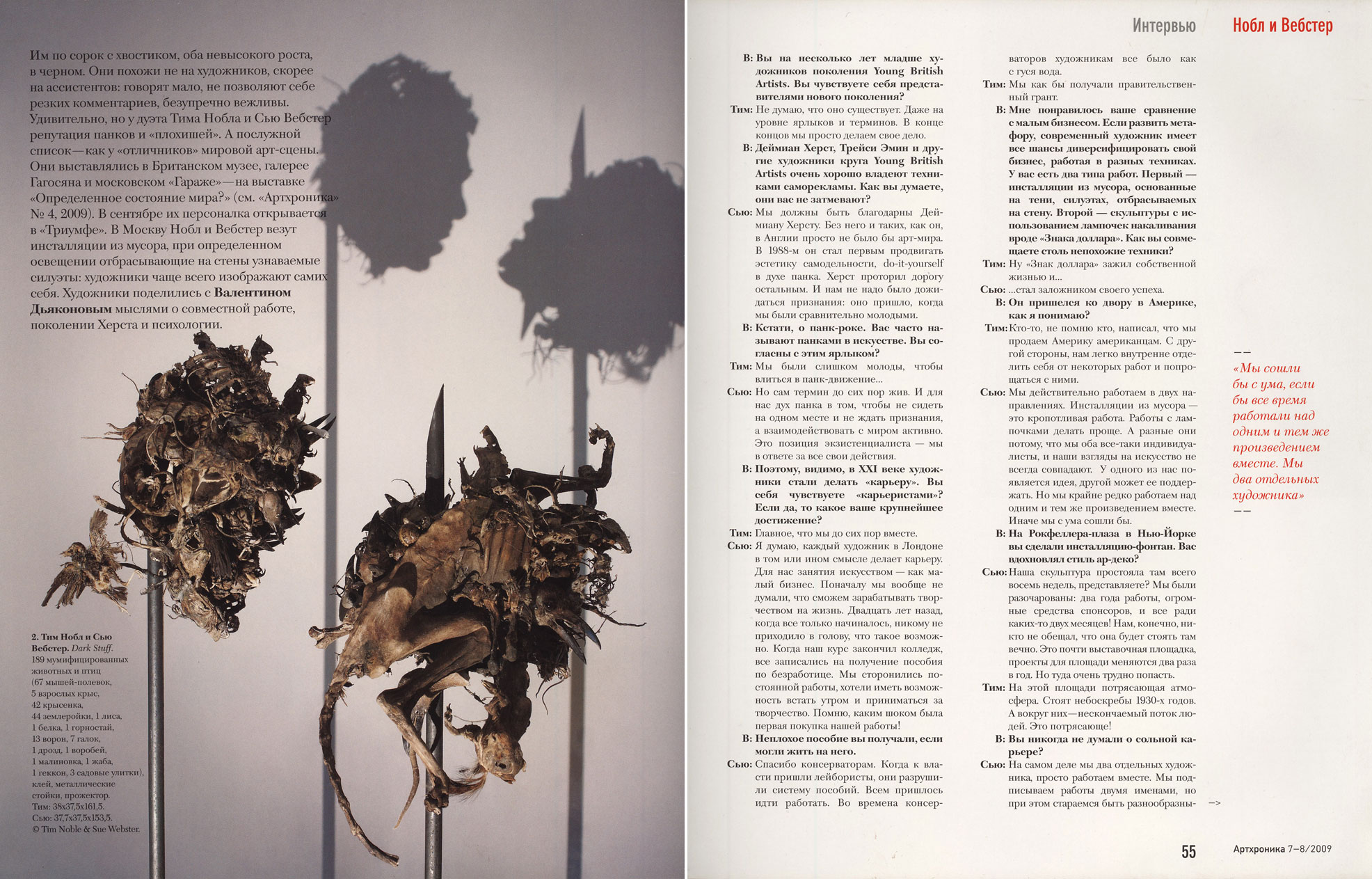

They're forty and a bit, both are short and dressed in black. They're more like assistants than artists: they don't talk a lot, don't make sharp statements, they're incredibly polite. It's surprising that Tim Noble and Sue Webster have the reputation of being punks and 'bad guys'. And a service record as 'high-achievers' on the international art scene. They've exhibited in the British Museum, at Gagosian Gallery and in the Moscow Garage, as part of the exhibition Un Certain Etat du Monde? (see ArtChronika 4/2009). In September their solo show opens at Triumph Gallery. Noble and Webster are bringing to Moscow installations made of rubbish which, when lit, throw a familiar shadow on the walls: more often than not the artists picture themselves. They shared with Valentin Diaconov their thoughts on working together, on the Hirst generation and on psychology.

V: You're a few years younger than the YBAs. Do you feel like representatives of a new generation?

Tim: I don't think it exists. Even on the level of labels and terms. In the end we're just doing our thing.

V: Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and the other artists in the YBA circle are very good at self-promotion. Do they think they overshadow you?

Sue: We're grateful to Damien Hirst. Without him and people like him there wouldn't be an art world in England. In 1988 he started to promote the aesthetic of do-it-yourself, in the spirit of punk. And we didn't have to wait for recognition. It happened when we were relatively young.

V: On the subject of punk, you're often called art punks. Do you agree with this label?

Tim: We were too young to be part of the punk movement . . .

Sue: But the term is still valid. For us the spirit of punk means not sitting still waiting for recognition but taking an active role in the world. It's an existentialist position – we are responsible for our actions.

V: That's why, apparently, artists started to make 'careers' for themselves in the 21st century. Do you feel like 'career artists'? If so, what's your greatest achievement?

Tim: The main thing is that we're still together.

Sue: I think every artist in London in one way or another makes a career for themselves. For us making art is like a small business. At first we didn't even conceive that we could make a living from art. Twenty years ago, when we'd just started, it didn't even enter anyone's head that such a thing was possible. When our year graduated everyone signed on the dole. We avoided permanent jobs because we wanted to get up in the morning and be creative. I remember what a shock it was when we first sold a work.

V: Unemployment benefit can't have been bad if you could live on the money.

Sue: Thanks to the Conservatives. When Labour came to power they destroyed the benefits system. Everyone had to find work. When the Conservatives were in power it was like water off a duck's back to artists.

Tim: It was as if we received a state grant.

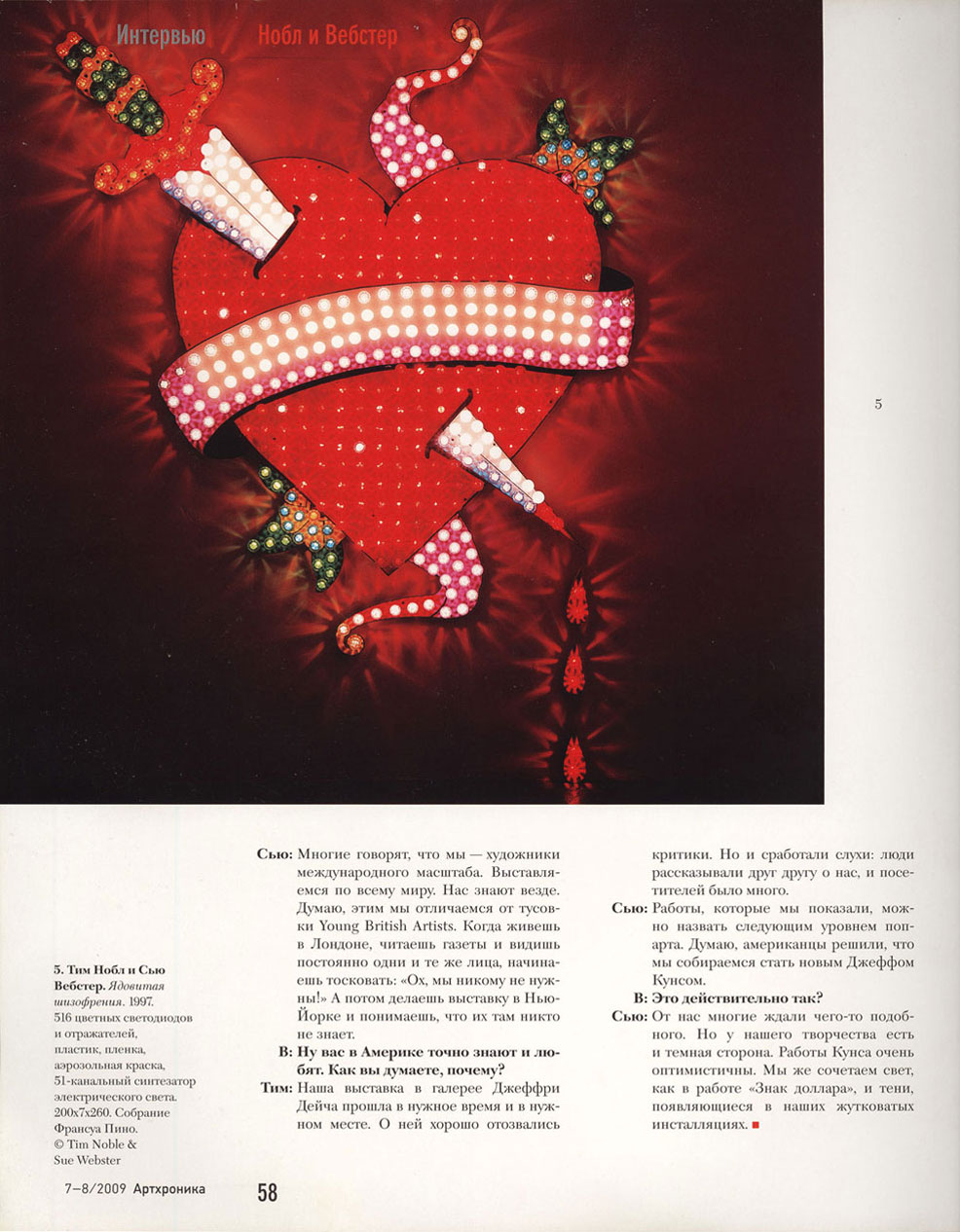

V: I like your comparison with small business. Developing the metaphor, a contemporary artist has every opportunity to diversify their business by working in various media. You make two types of work. The first is installations made from rubbish, based on shadows and silhouettes which are thrown on the wall. The second is sculptures using incandescent light-bulbs, like 'Dollar Sign'. How do you combine such different media?

Tim: Well, 'Dollar Sign' had a life of its own and . . .

Sue: . . . became a victim of its own success.

V: Didn't it work well in America, as far as I understand?

Tim: Someone, I can't remember who, wrote that we were selling America to the Americans. On the other hand, it's easy for us internally to separate ourselves from some works and say goodbye to them.

Sue: We actually work in two directions. The rubbish installations require painstaking work. The works with light-bulbs are easier. And they're different because we are both individuals and our views on art don't always coincide. One of us might have an idea which the other supports but we very rarely work together on the same piece. Otherwise we'd go mad.

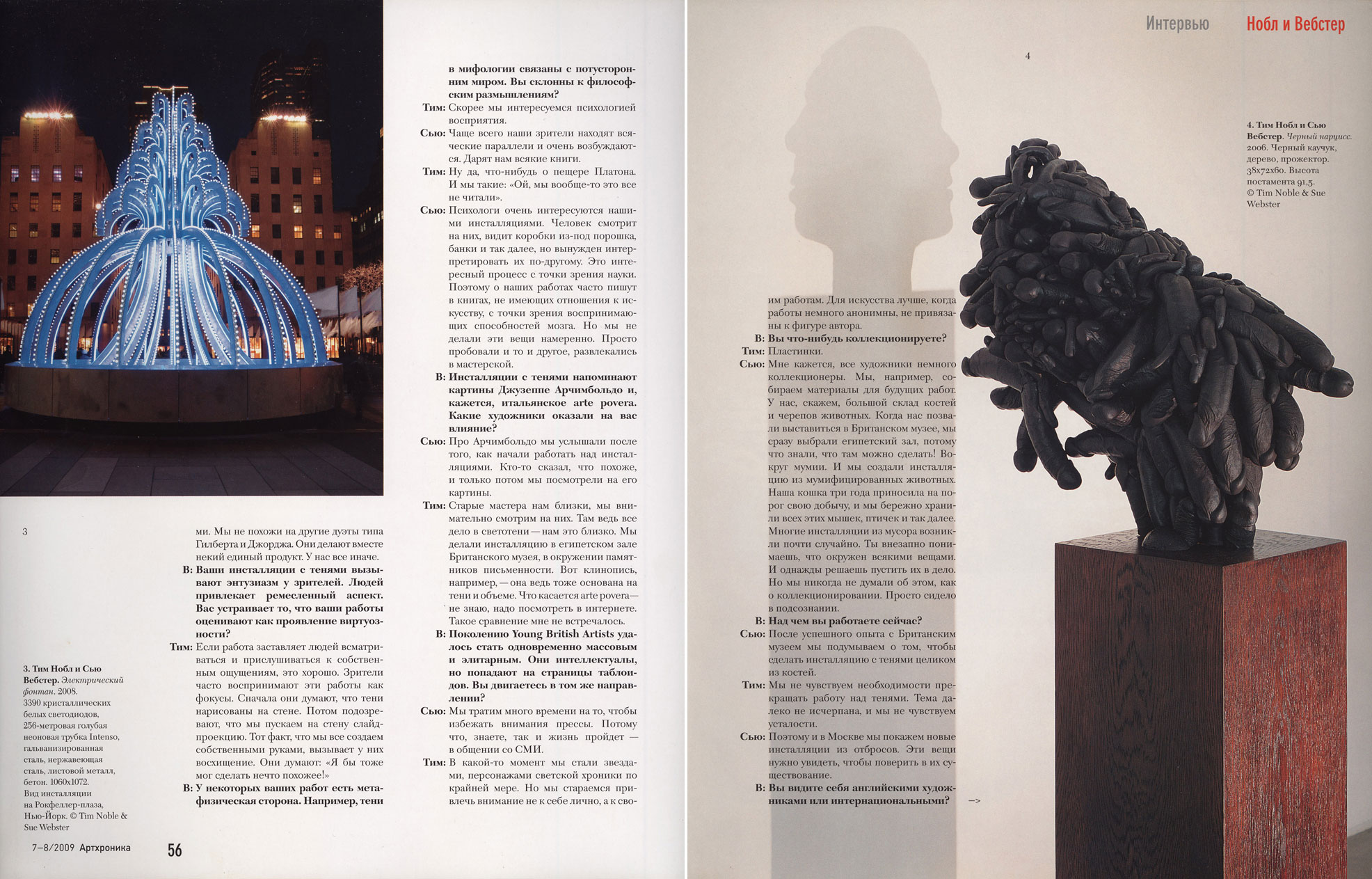

V: You made a fountain installation for Rockefeller Plaza in New York. Were you inspired by art deco?

Sue: Our sculpture was there for only eight weeks, can you believe it? We were disappointed. Two years of work, enormous investment by sponsors, all of that for two months! Of course we weren't promised that the work would remain there forever. It's almost an exhibition space, with projects changing twice a year but it's very difficult to be shown there.

Tim: There's an amazing atmosphere in that place. There are 1930s skyscrapers and around them an endless flow of people. It's amazing!

V: Have you ever thought about a solo career?

Sue: In fact we're two separate artists who simply work together. We sign our works with two names but even so we try to be different. We're not like other duos such as Gilbert and George. They work together on a single product. We work differently.

V: Your shadow installations really appeal to the public. People are attracted by the craftsmanship. Are you happy that your works are valued for their virtuosity?

Tim: If a work makes people look and listen to their own feelings that's good. Viewers often see our works as tricks. At first they think that the shadows are drawn on the wall. Then they suspect that we use slide projection. The fact that we make them with our own hands delights people. They think 'I could do something like that too!'

V: Some of your works have a metaphysical side. For example, in mythology shadows are linked with the other world. Do you think about philosophy?

Tim: We're more interested in the psychology of perception.

Sue: People often find such parallels and get very excited. They give us books.

Tim: Yes, something about Plato's cave. And we say 'Oh, we haven't even read that'.

Sue: Psychologists are very interested in our installations. A person looks at them and sees washing powder boxes, jars etc but is forced to interpret them differently. It's an interesting process from the scientific point of view. Our works are often written about in books which aren't on art, from the point of view of the perceptive abilities of the brain. But we didn't do that deliberately. We simply tried one thing and another and had fun in the studio.

V: The shadow installations are reminiscent of Arcimboldo and, it seems, Italian arte povera. Which artists had an influence on you?

Sue: People started to mention Arcimboldo after we began making installations. Someone said our work was similar and it was only then we looked at his pictures.

Tim: We like Old Masters and look very carefully at their work. Everything there is about light and shadow. We made an installation in the Egyptian room of the British Museum, surrounded by sculptures with hieroglyphics. Cuneiform, for example, is based on shadow and volume. I'm not sure about arte povera. I need to look at the internet. I've never come across such a comparison.

V: The YBA generation managed to be both mass-market and elitist. They're intellectuals but appear in the tabloids. Do you move in the same direction?

Sue We spend a lot of time avoiding press attention. Otherwise you spend all your time dealing with the media.

Tim: At a certain moment we became stars, or at least celebrities. But we try to draw attention to our work rather than to ourselves. With art it's better when the works are a little anonymous and not connected to the maker.

V: Do you collect art?

Tim: Records.

Sue: I think all artists are collectors. For example, we're gathering materials for future works. We have a large store of animal skulls and bones. When we were invited to show our work at the British Museum we immediately chose the Egyptian hall because we knew what we could do there! In that place there are lots of mummies and we made an installation from mummified animals. For three years our cat brought her catch to our door and we carefully kept all of these mice and birds. Many of the rubbish installations happened accidentally. You suddenly realise that you're surrounded by stuff. And one day you decide to use it. But we've never thought of it as collecting. It was just in our sub-conscious.

V: What are you working on now?

Sue: After our good experience with the British Museum we're thinking of making a shadow work with bones.

Tim: We don't feel the need to stop making shadow works. The subject is far from exhausted and we're not tired of it.

Sue: For that reason in Moscow we're showing new sculptures made from rubbish. You have to see these things to believe them.

V: Do you see yourselves as English or international artists?

Sue: Many people say that we're international artists. We're shown worldwide and known everywhere. I think in that way we differ from the Young British Artists crowd. When you live in London you see the same faces in the newspapers and start to worry, 'Oh, no-one needs us!', and then you do a show in New York and understand that no-one knows them.

V: In America people definitely know and love you. Why is that?

Tim: Our show at Jeffrey Deitch was in the right place at the right time. It got good reviews. And there was word-of-mouth – people told their friends about us and there were lots of visitors to the show.

Sue: The works we showed could be called the next level of pop-art. I think the Americans believed we were trying to be the next Jeff Koons.

V: And are you?

Sue: Many people expected something like that from us but our work has a dark side. Koons's works are very optimistic. We combine light, as in 'Dollar Sign' and shadow, which appears in our most terrifying installations.